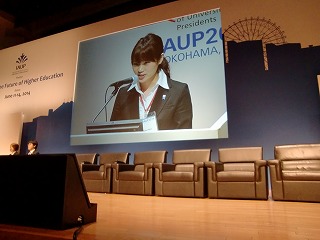

President Nakayama advocates the need for morality and ethics in higher education in a speech to the IAUP XVll Triennial Conference 2014

|

The XVII IAUP Triennial Conference was held from June 11th to 14th, 2014, in Yokohama, where President Nakayama participated in one of the concurrent sessions that took place on Friday the 13th. The theme of this session, which was chaired by Dr. Heitor Gurgulino de Souza, IAUP Secretary-General Emeritus, and co-chaired by Dr. Noriaki Sagara, Senior Vice President, JIHEE (Japan Institution for Higher Education Evaluation), was “Quality Assurance and Innovation”. |

In his presentation on “Actualizing Moral Education in Japanese Universities”, President Nakayama pointed out that universities today were required to respond to the need for a new kind of moral intelligence in their educational, administrative and research activities. Given that the twenty-first century is often described as the era of the “knowledge-based society,” wherein new knowledge, information, and technology assume ever greater significance in the fields of politics, economy, and culture, President Nakayama argued that it was not enough for universities to accept that the only task of higher education was to contribute to such a society by pursuing the maximization of knowledge. He contended that although the inhabitants of advanced countries may enjoy a fairly affluent lifestyle in the material sense, as well as having access to ever increasing amounts of information, the reality is that mental and spiritual anomie is increasing in tandem. For this reason, he said, “the mere enhancement of knowledge cannot deliver peace, security, and happiness to the people of the world; it cannot truly serve society unless it is accompanied by a high level of morality.”

In his presentation on “Actualizing Moral Education in Japanese Universities”, President Nakayama pointed out that universities today were required to respond to the need for a new kind of moral intelligence in their educational, administrative and research activities. Given that the twenty-first century is often described as the era of the “knowledge-based society,” wherein new knowledge, information, and technology assume ever greater significance in the fields of politics, economy, and culture, President Nakayama argued that it was not enough for universities to accept that the only task of higher education was to contribute to such a society by pursuing the maximization of knowledge. He contended that although the inhabitants of advanced countries may enjoy a fairly affluent lifestyle in the material sense, as well as having access to ever increasing amounts of information, the reality is that mental and spiritual anomie is increasing in tandem. For this reason, he said, “the mere enhancement of knowledge cannot deliver peace, security, and happiness to the people of the world; it cannot truly serve society unless it is accompanied by a high level of morality.”

As one illustration of this general point, he spoke of “the need for an ethic of science” in the following terms:

One interpretation of the history of science, which we may term the ‘heroic’ one, assumes a priori that science is so obviously a good thing that it need not allow itself to be subjected to ethical study. But science has had a negative as well as a positive impact on our society, as the Manhattan Project, biochemical weapons, and the impact of technology on the environment, among other examples, attest. If morality means respecting the characters and lives of others, scientists should think of those who have suffered negatively as a result of science and technology. So our concern with science has to include not merely its history and philosophy, but also its sociology, that is, the various modes of influence it has on society. Nor can we stop there. An awareness of how science influences society leads us inevitably to ask to ourselves what we should do next. This field of academic study, a sort of meta-science if you like, we may call the ethics of science. To argue thus is in no sense to be ‘anti-scientific.’

One interpretation of the history of science, which we may term the ‘heroic’ one, assumes a priori that science is so obviously a good thing that it need not allow itself to be subjected to ethical study. But science has had a negative as well as a positive impact on our society, as the Manhattan Project, biochemical weapons, and the impact of technology on the environment, among other examples, attest. If morality means respecting the characters and lives of others, scientists should think of those who have suffered negatively as a result of science and technology. So our concern with science has to include not merely its history and philosophy, but also its sociology, that is, the various modes of influence it has on society. Nor can we stop there. An awareness of how science influences society leads us inevitably to ask to ourselves what we should do next. This field of academic study, a sort of meta-science if you like, we may call the ethics of science. To argue thus is in no sense to be ‘anti-scientific.’

He concluded by referring to the views of Albert Einstein, who quoted approvingly (in a letter of 20th November, 1950) the inspiring words of Charles Dickens in Dombey and Son (ch. XXIII); “Only morality in our actions can give beauty and dignity to life”.